Complex trauma and colonial systems from a Two-Spirit perspective

CAITIE GUTIERREZ

Caitie is a mental health consumer advocate and writer from Lenapehoking (New York) who lives on Gadigal Country (Sydney). As a bisexual and biracial Biawaisa (Two-Spirit) Boricua (Puerto Rican) Taíno with complex PTSD and chronic illness, they draw on their lived experiences to explore topics like mental health, chronic illness, queerness, grief & loss, suicide, survivorship, intergenerational trauma, and ancestral healing.

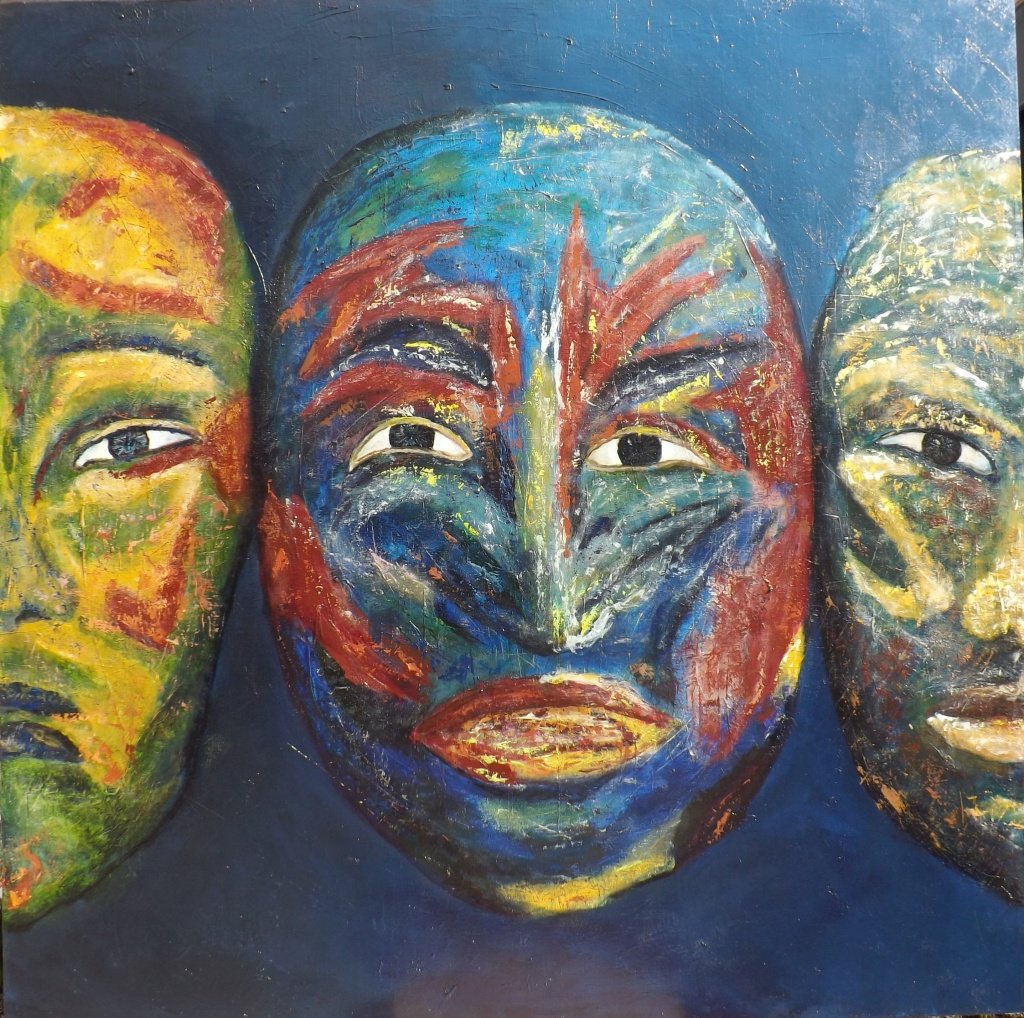

Artwork by a.c.ramírez de arellaño

“Two-Spirit” (often shortened to 2S) is a pan-Indian term created in 1990 that encompasses Indigenous cultural, spiritual, sexual, and gender identity. It is an umbrella term that is exclusive only to Indigenous cultures and was specifically chosen to distinguish and distance Native American/First Nations from non-Native peoples. Different tribes will use different terms for members who fulfill traditional third-gender or other gender-variant roles in their respective cultures. Two-Spirit is still being reclaimed and means something different for every Nation and person.

According to Taino Library, we as Taíno people are still in the process of redefining what Two-Spirit means for us because much of our culture was erased and/or hindered by colonisation. The power of Two-Spirit peoples, compounded by the fact that gender roles in Taíno culture were relatively non-exclusive, was a threat to the first colonisers who arrived in the Caribbean. The church did everything in their power to eradicate us. We have relied on oral traditions that have been passed down from our Elders, as well as looking to other Indigenous cultures who may have had less of their culture stripped away from them for guidance. Through language reconstruction, the current term used to describe Two-Spirit Taíno people in the yukayeke (similar to, but different than a “tribe”) I belong to, Higuayagua, is “Biawaisa.”

The term Two-Spirit or Biawaisa is not meant to be interchangeable with being LGBTQIA+, though many members of the community also identify with being LGBTQIA+. Our ability to take on the traditional roles of multiple genders make us sacred and respected members of our communities. Because of the spiritual nature of our identity, Biawaisa are often, but not always, assigned roles as healers. We have also been assigned roles as namegivers, matchmakers, war chiefs, and more.

Artwork by a.c.ramírez de arellaño

Growing up, I was disconnected from my Afro-Indigenous Puerto Rican culture through propaganda, psychological warfare, and forced assimilation. Similarly to what our Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander cousins have experienced, there has been a social, political, and economic push to “improve the race” towards a supposed ideal of whiteness. The cultural identity of Boricuas has been systemically attacked by the residential school system, academia, and paper genocide. The Taíno were declared extinct shortly after 1565 according to census records. There is also documentation of the race of Puerto Ricans being changed on census records during the first half of the twentieth century. I was able to find census records where my own family’s race was changed on paper.

Having our culture erased means that we often don’t receive the necessary medical care we require. As a bisexual Boricua Biawaisa with “invisible illnesses," the systemic erasure of my identities led to my mental and chronic illness going undiagnosed for far too long. The lack of proper healthcare I received until I was finally diagnosed (after 12+ years of complaining about symptoms to multiple doctors and psychologists) with Complex PTSD, PCOS (Polycystic ovary syndrome), and Endometriosis resulted in the likelihood of infertility. There is already a very heavy history of forced sterilization of Puerto Rican women. The systemic erasure of our culture, along with potential health risks passed down through intergenerational trauma, contributes to this ongoing history. On top of the fact that many people both within and outside of the United States don’t even know that Taínos still exist today, and that Puerto Rico is the oldest colony in the world (held captive by the United States government), we are forced to fight and advocate for ourselves - which proves to be difficult especially when you are already struggling with chronic health issues.

Although Complex PTSD was officially recognised by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2019, and there appears to be more recognition of complex trauma in so-called Australia than what I experienced growing up on Turtle Island (United States), it is still not recognised in the Diagnostic And Statistical Manual Of Mental Disorders (DSM) which hinders proper diagnosis and treatment for many. Complex trauma can often result in chronic illness, especially when left untreated. Approximately 84% of Native women and 78-85% of Two-Spirit individuals are abused in our lifetimes, with more than half of that abuse endured at the hands of an intimate partner. Indigenous people also face the highest rates of suicide out of any ethnic group in Turtle Island and so-called Australia.

I am a bisexual Boricua Biawaisa Taíno survivor of domestic violence, sexual abuse, and suicide. I kept my Biawasia identity between myself, my yukayeke, my partner, my loved ones, trusted health professionals, and other Indigenous peoples until I became a target of a harassment and smear campaign by a human trafficking cult. I was forced out of the closet when I almost became yet another victim of the Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit (MMIWG2S) epidemic. The Taíno were some of the first to become MMIWG2S when Christopher Colombus invaded the Caribbean.

Keeping this identity hidden comes from a long history of systemic erasure and trauma; a natural instinct that was passed down to me through my ancestors' unspoken need for safety and protection. We as Biawaisa and Two-Spirit peoples have been writing ourselves back into history, and the internet is one of our most powerful tools. Every Biawaisa and Two-Spirit person may relate to their identity and tribal roles differently, but we all carry on the legacy of our ancestors.

Wo do tuei wa hebeyo’no tabunho’aki tan. We are what our ancestors dreamed of.